An excerpt from the opening paragraphs of a 15 page magazine article about emigrants from the Azores and Cape Verde Islands who ultimately settled in Falmouth between 1880 and 1920 . . .

The Portuguese are notably absent from colonial and pre-colonial America, a surprising fact considering they launched the Age of Discovery and built an empire extending across more than half the globe, including parts of what are today fifty-three sovereign states, and lasting almost six centuries. They were excluded from the New World by treaties in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The only part of the New World available to them was eastern Brazil, and by 1760 — a generation before the American war of independence — 700,000 Portuguese were living there.

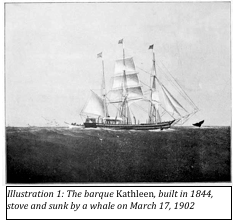

American immigration began in earnest when islanders from the Azores and Cape Verde islands arrived on American whaleboats like the barque Kathleen and some decided to stay. Most of these islanders were descended from immigrants of what is, in a sense, the first “New World”: the Azores, an early Portuguese discovery of nine islands 850 miles out to sea uninhabited at the time by man or any other land animal. The Azores were populated from Portugal, France, and England almost two hundred years before the Great Migration to Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies.

When the Pilgrims landed in 1620, the Portuguese had already been fishing off the Grand Banks for decades. It seems probable some individuals may have settled in the northeast before American whaleboats began calling on the Azores and Cape Verde islands, but it was not until then that Portuguese in any sizable numbers started immigrating in North America. Voyages typically lasted two to four years, and sailors did not get paid until the ship returned to port, unloaded its cargo, and paid each member of the crew a percentage of the profits. Many signed up for another voyage after spending some time ashore, some returned home, and some decided to stay. Initially, those who stayed lived primarily near whaling and fishing ports in New England and California, but some went to Hawaiian plantations and a few even journeyed to the California gold fields.

Like many ethnic groups, the intensely religious Portuguese tended to settle in areas with similar environments and familiar cultures. Waquoit village in Falmouth, bounded on two sides by rivers and on the third by the ocean, was a natural. At the time, Waquoit Bay was part of a thriving maritime economy. Falmouth itself, founded in a search for religious tolerance, had welcomed the Irish to Woods Hole, where St. Joseph Roman Catholic Church was built in 1882.

Falmouth’s economy changed significantly in the nineteenth century. The topsoil had become less productive, and the availability of cheap farmland on the expanding American frontier lured many residents away from Falmouth. Increased competition from a growing America, collapse of the saltworks, bankruptcy of the Pacific Guano Company, the extension of the railroad to Falmouth in 1872 further opening the town to competition, and the decline of whaling all took their toll. Cranberries offered new opportunities but it was extremely labor intensive, both in building the bogs and in harvesting the fruit, and Falmouth’s labor supply severely limited its expansion. Portuguese islanders were a big part of the answer for cranberries, fishing, farming, trades, and building local infrastructure. It became a truly symbiotic relationship, beneficial to both Falmouth and the Portuguese.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

This magazine is available at:

Eight Cousins Books, Falmouth, MA (508) 548-5548

Falmouth Historical Society, Falmouth, MA (508) 548- 4857